“The Longest View in the Room”

“To take the long view has an unintuitive advantage built in — fewer competitors.” — Sam Hinkie

“To take the long view has an unintuitive advantage built in — fewer competitors.” — Sam Hinkie

Disclaimer: this is by no means legal advice, simply sharing thoughts on a fascinating space and clarifying our own thoughts.

Overview

Throughout the first half of 2017, over $1.2 billion was funneled into over 50 different Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs). Due to the relatively sudden emergence of this new funding mechanism and investment vehicle, the SEC has been paying close attention. ICOs now sit in a state of regulatory obscurity. While there may be a short-term regulatory arbitrage opportunity here for prospective decentralized applications and companies looking to raise through an ICO, it will be short-lived. To borrow a quote from Sam Hinkie, the protocols and applications that thrive will be those whose founders move forward with “the longest view in the room.”

An Alternative Funding Mechanism

There are a number ways for early-stage companies to raise capital today, namely IPOs, private placements, and venture capital or private equity financing. Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) are an alternative fundraising mechanism, which have garnered massive publicity over the last year. Similar to equity crowdfunding, this process enables decentralized organizations to issue tokens or coins, commonly referred to as cryptoassets, to prospective investors. This vehicle allows investors to generate returns based on the appreciation of value of the underlying network, which the cryptoassets represents. While traditional financing outlets have prevailed over the past few decades, ICOs have risen in popularity because of several unique characteristics.

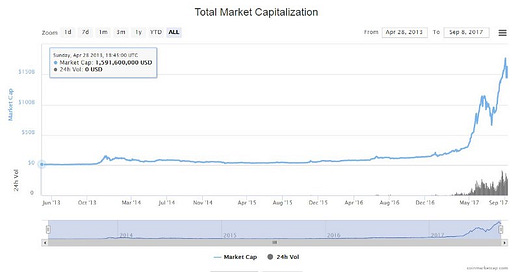

To start, the return prospects for cryptoassets[i] originated through ICOs have been unprecedented. Ethereum, the first ICO (then referred to as a “token sale”) launched in July, 2014 and has returned 94,129% as of September, 2017. The total market capitalization of cryptoassets has skyrocketed over the past few years, as demonstrated by the figure below. The investment returns have led to the amassing of large amounts of digital wealth for investors in Bitcoin, Ether, and other cryptoassets. That allure has certainly contributed to the wild investor demand for subsequent ICOs.

Cryptoassets are also uncorrelated assets, providing some portfolio diversification against conventional asset classes. Cryptoassets derive their value from the underlying protocols[1] upon which their representative applications are built. As a result, the global macroeconomic environment, interest rates, and international currency fluctuations do not impact their underlying value. ARK Invest, a New York-based investment research firm, describes in a white paper that “Bitcoin exhibits characteristics of a unique asset class — meeting the bar of investability, and differing substantially from other assets in terms of politico-economic profile, price independence, and risk-reward characteristics.” [2]

Additionally, cryptoassets are non-dilutive, unlike traditional venture capital financing. Over the last few decades, startup companies have tended to raise equity capital, which typically is diluted over subsequent fundraising rounds. In other words, original ownership is diminished as additional investors commit capital. However, the concept of “dilution”’ isn’t applicable for tokens as they aren’t considered equity. As a result, investors’ ownership stake does not decrease as subsequent investors buy new tokens; the purchasing power of a token won’t diminish as more are issued.

Lastly, there is an unmatched liquidity premium that exists for cryptoassets. These tokens and coins are tradeable on secondary exchanges immediately after initial purchase through an ICO. Conversely, venture-backed startups often must wait years until a liquidity event such as an IPO or an acquisition occurs. Aswath Damodaran, a foremost expert on asset valuation and a professor at NYU, observed that there has historically been a 20–30% discount for illiquid assets[3]. Furthermore, there has been a large drop off in the number of public companies. According to research from Credit Suisse, “the propensity to list is now roughly one-half of what it was 20 years ago. The net benefit of listing has declined.”[4] Due to the diminishing rate of IPOs, the benefits of a traditional public offering have become less clear. It is far more difficult for early investors and employees to realize returns with this reduction in liquidity events. This reiterates the opportunity presented for non-traditional types of fundraising.

It’s important to note that tokens derive their value from the underlying strength and development of the protocol or overlaying dApp[5] which the token represents. While most assets have a speculative worth, the real value of cryptoassets lies in the underlying network upon which it is built. Most assets are a function of supply and demand; however, the success of cryptoassets also depends on the functional adoption and development of the underlying network protocol.

Through the Lens of the SEC

ICOs have thus far been in uncertain territory through the lens of the SEC. The Decentralized Autonomous Organization (“DAO”), which raised $150M through their ICO in May, 2016 was the victim of a $55M hacking attempt last June. While most of the money was recovered by the rightful owners, the event spurred an SEC investigation to determine what went wrong and how to prevent similar issues. In July of 2017, the SEC returned with a press release stating that in the instance at hand, the tokens sold by the “DAO” were, in fact, securities, subjecting them to traditional securities legislation under the Securities Act of 1933. This statement has since prompted uncertainty around whether the ruling will be broadly applied to all ICOs. As a result, many ICOs have prevented access to U.S. investors.

The Howey Test exists as the legal framework to determine whether or not an asset is a “security.” This test focuses on four key questions: (A) is there a financial investment? (B) Is the investment in a common enterprise? © Is there an expectation of profits? (D) Are the profits derived primarily from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others? While there is some ambiguity around the latter two components, the recent SEC ruling has presented a lot of controversy around the ultimate legal definition of cryptoassets. If a cryptoassets is deemed a “security,” then the offer and sale via ICO are subject to the standard securities laws.

Opportunity for Issuers Seeking U.S. Capital

ICO issuers should avoid being short-sighted, instead pursuing issuance strategies with a long-term regulatory horizon in mind. Considering recent events and increasing investor demand surrounding ICOs, it appears that issuers of digital currency issuers need to assume tokens are securities if they intend to seek U.S. investors. The statement below from the recent SEC press release reiterates the need to proceed with caution:

“The DAO” were securities and therefore subject to the federal securities laws. The Report confirms that issuers of distributed ledger or blockchain technology-based securities must register offers and sales of such securities unless a valid exemption applies. Those participating in unregistered offerings also may be liable for violations of the securities laws.”[6]

Fast forward two months to September; On the 1st of September, U.S.-based Protostarr, was contacted by the SEC during their live raise. After legal consultation, Protostarr ultimately decided to cease its raising efforts. Three days later, China’s Central Bank deemed ICOs as illegal, mandating a halt and elimination of all coin offerings in its country. China’s government cited the ongoing and unchecked fraud taking place in this burgeoning market, deeming it unsafe and too risky for continued investment.[7]

These three recent developments indicate the unregulated grey area is shrinking, both domestically and globally. ICO issuers seeking U.S. capital should take notice. Failure to comply may not only be detrimental to individual issuers, but could result in steeper oversight and subsequent regulation over the entire U.S. ICO community. In the end, this could limit its growth potential.

Recent financial markets history should remind us of negative impacts of over-corrective legislation. Financial deregulation beginning in the 1980s helped to spur a prosperous few decades for mortgage financing and securitization. The systemic subprime mortgage fallout in 2007 carried with it a severe regulatory reaction in the form of overtly, strict legislation such as Dodd-Frank. The increased capital requirements and compliance costs that Dodd-Frank carried with it have dismantled innumerable community banks across the U.S. The lack of regulation invited excessive risk taking, which lead to a crash followed by an over-corrective, arguably excessive regulatory response. This should serve as a lesson to the broader ICO community; standardized and easily monitored processes can help to avoid the adverse effects of deregulation. Fortunately, these processes already exist in the parallel world of equity crowdfunding through regulatory exemptions. And ICO issuers should again, take notice.

ICOs can be construed as a form of crowdfunding, theoretically allowing them the same exemptions available in the equity crowdfunding space. More importantly, the SEC has yet to denounce this regulatory route, thus exemplifying “a valid exemption applies.” For U.S. issuers of digital currency, these regulatory exemptions come in various forms:

Regulation D, Rule 506: Reg D, Rule 506 allows issuers to raise an unlimited amount of capital from accredited investors if the SEC is notified within 15 days after the initial raise. The notification comes in the form of an online filing, referred to as a Form D. [8]

Regulation CF: Reg CF allows U.S. companies to raise up to $1 million from both accredited and non-accredited investors in a 12-month period. Issuers using Reg CF are required to file a Form C as well as disclose a myriad of information to potential investors, including financial statements, market risks and a business plan.

Regulation A+: Reg A+ allows U.S. or Canadian companies to raise up to $50 million from accredited and non-accredited investors. In this case, issuers must file a Form 1-A and comply with a semi-annual review process and annual auditing. However, Reg A+ gives the companies the options to launch a “mini-IPO” process, where their raise can be publicly advertised.

These exemptions enable U.S. issuers to raise from both accredited and non-accredited investors at an extremely low, relative cost. According to our research, legal costs of filing Reg D regularly do not exceed $1,000. Reg CF and A+, although higher, remain at controllable levels, typically costing issuers roughly between $10,000-$20,000 and $45,000-$50,000 respectively. Although seemingly high, these filing expenses are marginal compared to the millions of dollars startups typically cough over to investment banks, accounting firms and attorneys through fees in the traditional IPO process. They’re also insignificant compared to potential fees and ramifications issuers could face if the SEC commences a cyclical crack down.

These exemptions also give everyone a seat at the table, thus democratizing this new investment opportunity. And depending on the type of exemption, issuers are given the option to raise from both accredited and non-accredited investors via side-by-side offerings. This will prove paramount in a field drawing a high amount of millennial attention.

What if foreign issuers are seeking U.S. capital? After all, one of the most successful ICOs to date, Ethereum, did originate in Switzerland and many have followed suit. Enter Reg S and the previously mentioned side-by-side offering. For starters, Reg S, the “safe harbor” exemption, characterizes a raise executed in another country, thus not subject to any SEC regulations. However, foreign issuers can execute two distinct raises of their digital currency through a concurrent offering in parallel with Reg D, known as a side-by side offering. This raising route gives them access to both U.S. and international capital pools. The same methodology can also be applied to domestic raises where U.S. issuers desire access to both accredited and non-accredited investors, such as a concurrent Reg D and Reg CF raise.

For this approach to scale, there is a need and opportunity for online platforms, both issuer and investor-facing, that provide access to these exemption-based ICOs. CoinList and Waves are currently the only technology platforms in the market that allows both issuers to list coin offerings and persons to invest. However, neither are FINRA registered broker-dealers, meaning they cannot facilitate Reg CF or A+ raises, only Regulation D listings. Because of this, legal mechanisms for investing remains limited to accredited investors at this point. But if equity crowdfunding’s recent flourishment of online platforms and broker-dealers over the past 3 years is any indication, we could see ICOs start to shift in the same direction. This is something we believe that will both legitimize and standardize this alternative asset class, which currently remains in its regulatory infancy.

[1] Protocol: a protocol is standard language that allows people to collectively work on problems (i.e. HTTP, TCP/IP)

[2] Bitcoin: Ringing The Bell For A New Asset Class, ARK Invest, http://research.ark-invest.com/bitcoin-asset-class

[3] The Cost of Illiquidity, Aswath Damodaran, NYU

[4] The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks, Credit Suisse, Michael Mauboussin

[5] dApp: a “decentralized application” is an application built upon a protocol

[6] http://www.sec.gov/new/press-release/2017-131

[7] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-04/china-central-bank-says-initial-coin-offerings-are-illegal, https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurashin/2017/09/01/after-contact-by-sec-protostarr-token-shuts-down-post-ico-will-refund-investors/#6c5b2262192e

[8] Accredited Investor characterizes someone who makes at least $200,000/year or has a net worth exceeding $1 million, excluding home equity