Will Banks' Fee Income Follow a Similar Path to Brokerage Commissions?

What does the future hold for service charges and overdraft fees

Challenged Revenue Profiles for Banks

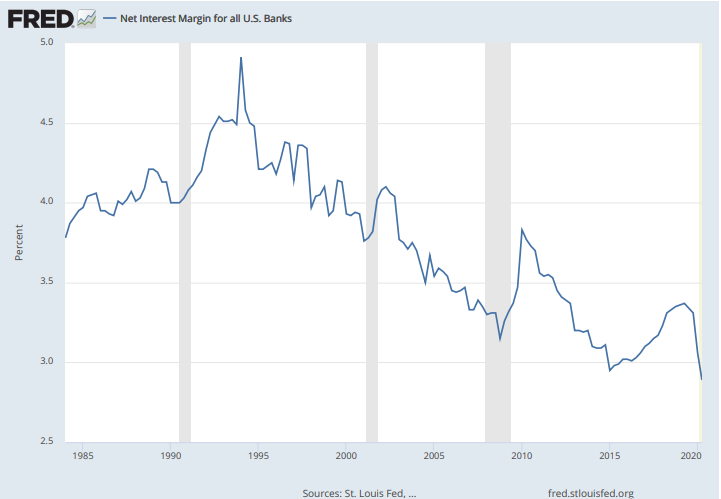

Amid record-low interest rates and a reticent consumer credit environment, banks sit in an uncertain position as markets weigh the potential outcomes from a prolonged pandemic into 2021. Most major US banks have reported a compressing net interest margin, or the spread between interest earned and interest paid, a trend that has persisted since the late ‘90s.

The pandemic has in many ways been a boon for bank balance sheets, who have benefitted from impressive deposit growth since the first quarter of this year driven by a shift from spending to savings and government stimulus relief efforts.

Furthermore, while fears of diminishing credit quality have proliferated amid higher unemployment figures and small business failures, consumer credit has been resilient through the Q3’20.

“The credit performance has been extraordinarily good given where we stand." - Charlie Scharf, Wells Fargo

"We continue to see very stable performance from a credit point of view. And the short of it I think and I’ll take it through a little bit of it, but we are probably more likely to see releases when I think about reserves than we are to see build, is the way things have been trending.” - Mark Mason, Citi

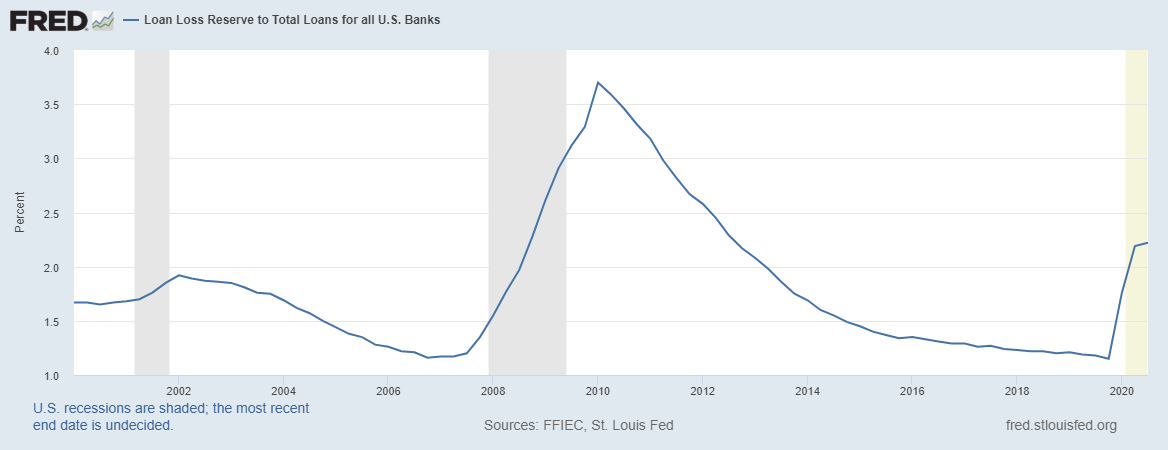

Going forward, however, the health of the consumer is undoutbedly a concern as evident by the billions of dollars banks have set aside for loan loss reserves. While most of those loan losses won’t be realized until the latter half of next, charge-offs are a looming concern for lenders.

Based on recent comments from Jamie Dimon, the rate of consumer savings may be challenged in the coming months:

“Today you see savings balances are way up, okay, and the people could afford homes, they're buying a lot of homes and mortgage prices are way down and you see the activity that creates. But for the bottom quartile, the extra cash that came in because of the unemployment checks, that's gone. They’re now at the point where they may have to start cutting their spending.”

More recently, loan volume has fallen precitiously. Underwriting standards have been raised in anticipation of future challenges on the credit side.

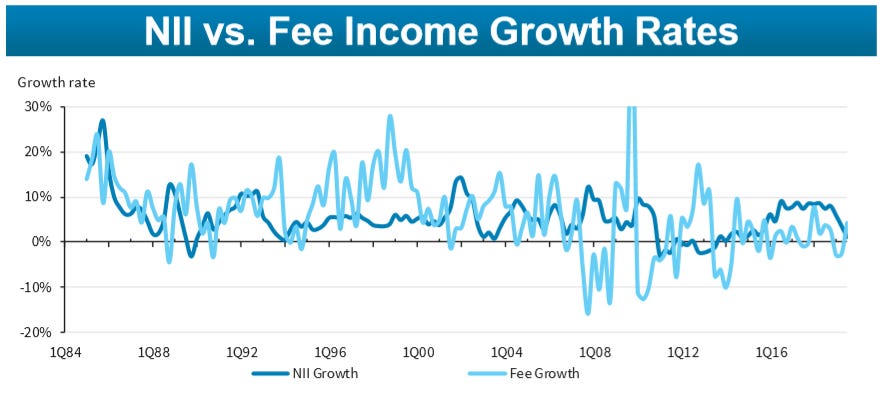

Historically, when low rates challenge net interest income, banks tend to rely more on the non-interest income to diversify revenue drivers. A Fed paper found that banks increase their dependence on service charges when NIMs decline, which lines up with conventional logic.

But there’s a case that the trends for non-interest income in retail banking are heading in one direction.

That is all to say that, in the midst of Covid-induced uncertainty, the next few years will pose persistent challenges for banking revenues as interest rates remain low.

Trends in Non-interest Income

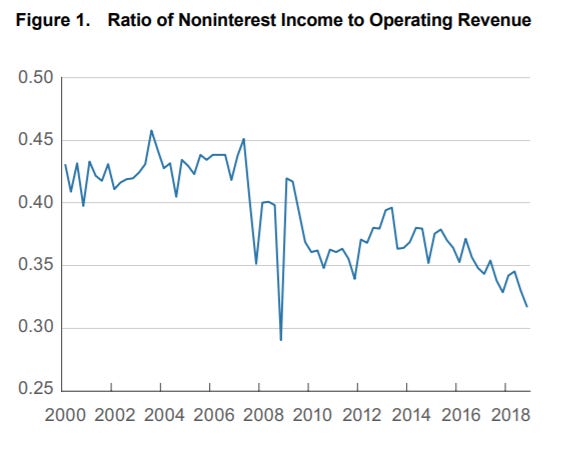

Banks generate roughly a third of their total revenues from non-interest income. Practically speaking, that means service charges, overdraft accounts, origination fees, and investment banking fees.

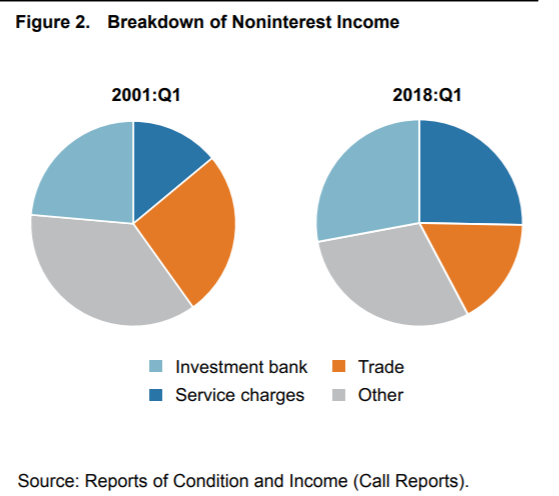

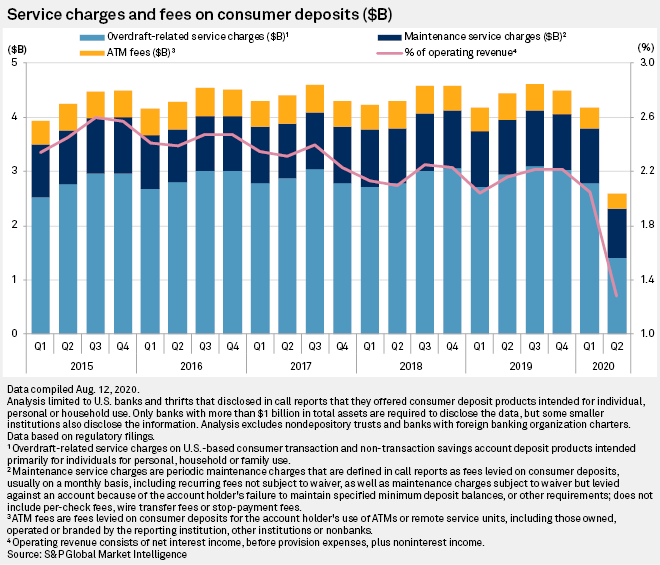

While the ratio of non-interest income to total operating revenue has declined by ~10% since 2000, it still represents a sizable portion of banks’ top lines. Most relevant to retail banks, service charges have nearly doubled from 14% of noninterest income in 2000 to 25% in 2018.

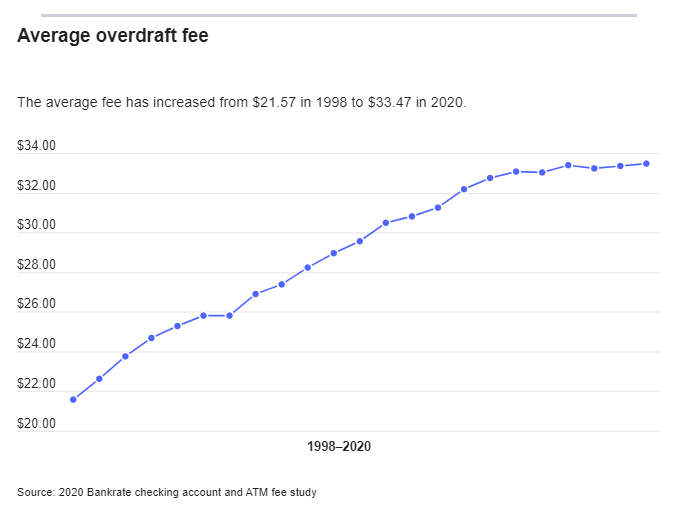

While the spreads on interest rates on loans and deposits drive the lion’s share of revenue, non-interest income is more consistent and stable. It is also a driver of consumer’s distaste for banks, which has continued to grow since the global financial crisis. The figure has risen in recent years, with reports suggesting it reached upwards of $34B in 2017.

Banks have been buoyed by trading and investment banking fees in the past few quarters — with FICC, ECM, and DCM revenues near 10-year highs. On the retail banking side, however, the challenges have been more apparent.

Fee income has taken a hit this year due to a combination of heightened deposit growth, lower transaction volumes, reduced cash usage, and waivers. Overdraft fees fell nearly 50% in Q2’20.

While those figures are likely to bounce back towards historical norms, several themes suggest that the drag on non-interest income from retail banks will persist after Covid-19.

Attacking the ~$34B profit pool

Amid the combined challenges coming from consumer pushback and startup activity attacking this profit pool for banks, roughly $34B annually, from venture-backed challenger banks and technology companies entering the banking sector. These companies are often appealing to a lower-income demographic, often Millennial and Gen Z customers who have either never had a previous banking relationship or are underwhelmed by their current one.

Challenger banks have used service fees as a wedge to steal customers from larger banks. One of Chime’s leading customer acquisition channels is unhappy Wells Fargo customers. Transparent, no-fee offerings clearly have a place in the market, as evident by the continued customer adoption from Chime, Cash App, Varo, and MoneyLion. Collectively, these companies have amassed tens of millions of users, many of whom rely on challenger banks as their primary bank.

A no-fee offering is likely more of a pricing feature rather than an explicit product. Overdraft protection isn’t new, but it has increasingly become table stakes among the leading consumer fintech companies. Similarly, low-cost secured bank and card accounts have been offered by banks for years.

I’m a little less bullish than most on the myriad of challenger banks, as I believe many of them are simply reinventing the wheel. Nonetheless, the pressure stemming from a growing number of well-capitalized startups may be an impetus for reevaluation from incumbent banks .

A few examples below:

Wells Fargo: “Deposit service charges, my sense, will be lower because of actions that we’re taking on a targeted basis to reverse fees where it’s appropriate.” - Q1’20

Huntington Bank: “Again we've seen kind of a flight to quality and flight to proximity from our customers and leveraging Huntington as a place to hold those deposits. So, I think that's going to hold personal service charges lower for a while. It's really not our focus for growth. We're really driving the value-added fee lines over time." - Q3’20

PNC: “Growth was across all categories except service charges on deposits. The $12 million or 2% decline in service charges on deposits was reflective of our ongoing efforts to simplify products and reduce transaction fees for our customers.” - Q1’20

Bank of America: launched Balance Assist, a short-term, low-cost loan to help consumers manage liquidity needs - Q4’20

Wells Fargo: launched limited-fee account, Clear Access Banking, with a $5 monthly fee and no overdraft fees - Q3’20

J.P. Morgan Chase: launched Chase Secure Banking, with a monthly service fee of $4.95 and no overdraft fees

While these are simply anecdotes and product launches today, this may indicate a broader trend of a departure from service charges and overdraft fees on banks’ income statements down the road.

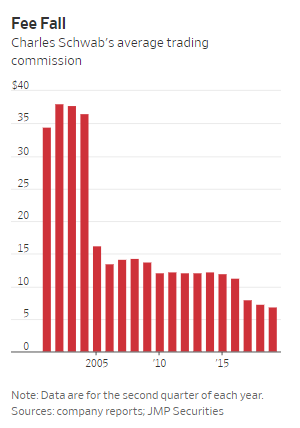

Will the long-term path for bank service charges emulate that of brokerage commission fees?

To me, this raises a question around the potential for bank service charges to emulate a similar trajectory to that of brokerage commission fees. While the models, products, and history of the fee structures are different — the underlying catalyst for change may very well be the same: the drive to lower the cost of consumer financial services.

Faced with mounting competition from online self-directed brokerages like Robinhood, Schwab announced that it would cut commission fees to zero in October of 2019. Commoditization and compeition drove the decision, which was promptly followed by TD Ameritrade, E*Trade, and Interactive Brokers.

The potential impact of a similar decision to do away with service charges and overdraft fees would be good for customers and bad for banks. There is also a risk that comces from inaction. Challenger banks have paved the way for more widespead adoption of no-fee bank offerings. Incumbents who fail to act risk churning customers and impaired reputations. Schwab’s move was defensive and immediately detrimental to its business model, but the rationale was also strategic:

“We don’t want to fall into the trap that a myriad of other firms in a variety of industries have fallen into and wait too long to respond to new entrants…It has seemed inevitable that commissions would head towards zero, so why wait?” — Peter Crawford, CFO of Charles Schwab

It’s way too early to say that the same phenomenon is inevitable for banks. Simply something to follow going forward, as the possibility has significant implications for banks.

Consumers will ultimately vote with their wallets — the inertia associated with changing banks prevents most consumers from switching, regardless of how they feel about their primary bank relationship. As a result, less than 5% of consumers change banks in a given year.

So far this year, service charges and overdraft fees,have taken a hit as card engagement and cash usage have both fallen while savings have jumped during the pandemic.

Given the rapid competition in consumer financial services from fintech companies and non-banks, there’s an interesting parallel with brokerage commissions that suggests retail banks’ fee income will continue to decline moving forward.