Are Money Managers a Commodity?

Written by: David Perell and Conor Witt

Update: Great response from Josh Brown here and Barry Ritholtz here.

“Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.” — Yogi Berra

Money managers are a commodity. The rise of quantitative investment strategies (computers), more equal access to information (the internet) and other factors have leveled the playing field. The threats posed by low cost investment vehicles and the abundance of talented managers are challenging the ability for the traditional asset and wealth manager to deliver value.

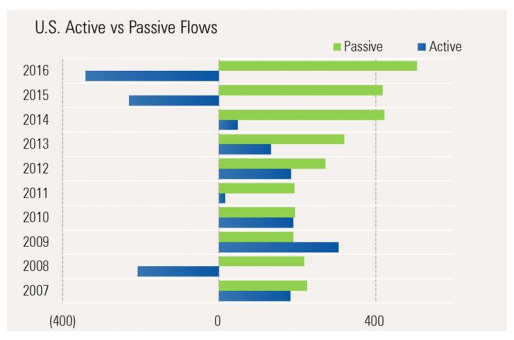

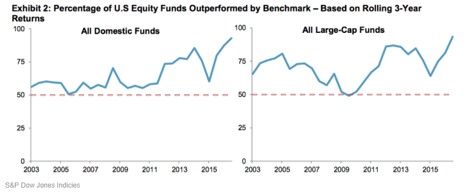

On average, active managers don’t deliver the value they claim to provide. In 1990, Bill Sharpe, a Nobel Prize winner for economics outlined the Arithmetic of Active Management, arguing that after fees, passive investing strategies outperform active ones. This is even more true today. Most investors are better off with low cost index funds. Investors have responded in waves — ETFs and index funds have exploded in popularity over the past decade.

The vast majority of active managers have underperformed during the past five years, according to S&P data. In response, many investors have moved from active management, towards index funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs).¹

Passive investments now total $6 trillion, according to Moody’s. That’s a steep increase from less than 1% 30 years ago. Warren Buffett, who made his fortune through the selection of individual businesses, believes amateur investors can outperform most investment professionals by simply investing in index funds.

To be sure, active managers play a critical role in capital markets, providing liquidity and price discovery. However, active managers are handicapped by higher fees, transactions costs, and taxes. As a result of this cost hurdle, active managers, on average, have been unable to outperform passive indexes.²

The traditional edges of money managers are also disappearing. A compelling explanation comes from Charley Ellis, the founder of Greenwich Associates, Chair of the Yale Endowment, and Director Emeritus at Vanguard. In a 2016 interview discussing the changing investment landscape since the 1960’s:

“Massive change [has occurred] in virtually every variable. Just for an example: if you go back, 50 years ago there might have been 5,000 people involved in active investing. Now there are at least a million involved. And they’re smart. Well educated. They’ve all got exactly the same tools. Computers, access to the internet, Bloomberg terminals, and they’ve all got access to the same information because the SEC requires public companies to give everybody all the information they give to anybody.”

Due to talent and technology, is has become more difficult to beat the market. The level of absolute skill has never been higher, but the dispersion of relative skill across managers is shrinking. As a result, luck — not skill — increasingly explains the success of active managers. It follows that predicting which active managers will be successful is increasingly difficult.

Because of these changes, firms must find new ways to retain and grow client assets. Historically, firms have generated demand through past performance, advertising, geographic location, and social proof. Access to information was limited and expensive. Information asymmetry, local laws, and language barriers reduced competition. These advantages helped to justify the costly fees charged by money managers.

But today, these advantages are dissipating. Fee compression, digital advice, the proliferation of passive, access to data, and increased competition have leveled the playing field. As a result, asset and wealth managers face an uncertain future.

So, if your job is managing money for clients, how do you differentiate yourself?

Shifts in society begin with shifts in the way we communicate. New technologies reshape the flow of human communication and transform our perception of the world. The shape of information flow largely determines the structure of society, and by extension, the flow of capital through it. To that end, societies have always been shaped more by the nature of media than by the content of it.

These communications shifts have continuously transformed the finance industry. In 1790, before the creation of the New York Stock Exchange, President Alexander Hamilton announced his plan to restructure the national debt. Upon hearing the news, speculators purchased bonds at favorable prices from Southern holders who had not yet heard the news. Traveling to the South by ship, speculators outpaced the spread of the news, which traveled by land.

In 1866, undersea trans-Atlantic cables connected the U.S. to Europe for the first time. Markets became more efficient as price information became more available. Stock exchange participation increased as investors bought and sold stocks with telegraphs. “Telegraph boys” recorded these transactions, sprinted to telegraph boots across the floor to execute transactions. Telegraphs were unaffected by weather and road conditions, and as a result, telegraphs worked almost 100% of the time. Telephones were first installed in the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 1878, which gave investors direct access to brokers on the floor of the exchange.

Before these inventions, investing practices and marketing tactics were constrained by time and space. The size of groups, or the number of people who could work together was limited by “Dunbar’s Number,” which states that groups of more than 150 people require institutional and technological innovations to cooperate effectively. But by removing technological limitations, modern communications technologies have transformed investing from a lethargic local affair to an instant global one.

As Morgan Housel recounted, people invested in what and who they knew. The capital system did not travel or scale well. There were technological reasons for this — the SEC didn’t keep corporate documents in electronic form until 1984. Bill Bernstein wrote about investment strategies in the 1800s: “They matched borrowers and lenders only by word of mouth or dumb luck — even though the two parties most often lived in the same city. As a result, both the users and suppliers of capital could not easily ascertain the true cost of capital, and because of this uncertainty, both sides were reluctant to transact.” Historically, investing has been a local affair, and only after the invention of new communications technologies in the 1980s, did it become a global one. As a result, firms spent less time marketing locally and more time marketing globally via blogs, podcasts, and television appearances — all of which are made possible by the ease of content creation and free, instant global communication.

As technology and policy changes have increased information flow and removed geographic constraints, firms have adopted new ways of attracting clients and demonstrating their value to them. Attention has become thedefining point of differentiation. To that end, leading firms have openly disclosed their investment strategies. Today, this is controversial but in the future, it will be commonplace. Using trust as a competitive advantage, modern firms are guided by transparency, ownership of attention, and consistent communication with current and prospective clients. We call them Naked Brands.

Two firms, Cambria Investments and Ritholtz Wealth Management, stand out from their competition. Few firms command trust and attention like Ritholtz and Cambria. Through candor, authenticity, and consistent content creation, they are blazing the trail for future managers.

In 2016, Ritholtz Wealth Management was named one of the fastest growing financial advisory firms in 2016 by Financial Advisor Magazine. Four years after its founding, Ritholtz Wealth Management manages more than $500 million in assets. Called the “Wu-Tang Clan of Finance,” Ritholtz Wealth Management (RWM) is a collection of prominent financial bloggers. Barry Ritholtz, the founder of the firm, started blogging in 1998 out of frustration with misleading and superficial mainstream market commentary.

Through decades of sharing authentic perspectives through a myriad of channels, RWM has earned the trust of audiences and defined its investment philosophy. They’ve bypassed traditional media outlets and reach their audiences directly. As a result, the firm defies tradition. A recent quote from RWM CEO Josh Brown cuts to the heart of the Naked Brands thesis: “financial services was always sold on the basis of the reputation of the firm. And it’s not that that’s not important anymore. It’s [about] personality…people don’t follow brands, they follow people.” By fostering communication between advisors and investors, podcasts are the new word-of-mouth, and blogs are the new business cards.

“In the history of Wall Street I think there are two types of firms — I think there are firms…where you’re putting out products that you believe in, you work your ass off to make them the best possible products, you put your own money in them, and you build a culture that these are things you believe in. Then you have a lot of firms…that will put out whatever they can to capitalize and make as much money as they can on the themes of the day.” — Meb Faber

Cambria Investments is an investment management firm in Los Angeles co-founded by Meb Faber and Eric Richardson in 2007. Meb is a prolific writer, researcher and hosts his own podcast. His first white paper “A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation” has been downloaded more than any other white paper. Meb is an active proponent of ETFs, low cost investing, and the democratization of institutional investment strategies to retail investors.

Through consistent communication — regular podcasts, blogs, and white papers — Meb is transparent about his investment philosophies and his firm’s point of view. With a small staff and no marketing budget, marketing is a major component of Meb’s job. He described his strategy in a recent interview: “Content is sales. We put out a bunch of the content and people find us.” The firm just passed the mark of $1B in assets under management, largely due to their ability to connect with readers and clients on a daily basis.

While index funds and ETFs will likely continue to attract fund inflows, people still need personal advisory on their investments. Ritholtz Wealth Management and Cambria Investments have both used social media and original content to build relationships, express their investment philosophies, and generate trust at scale. Building on the pillars of Naked Brands — transparency and consistent communication — wealth managers can differentiate themselves, attract a global clientele, and justify their fees.

This route of authenticity has propelled numerous public and private wealth managers and investors. Some of our favorites below:

Ritholtz WM — Barry Ritholtz, Josh Brown, Ben Carlson, Michael Batnick, Bill Sweet, Kris Venne, Tony Isola

Cambria Investments — Meb Faber, Jeff Remsburg

O’Shaughnessy Asset Management — Jim O’Shaughnessy, Patrick O’Shaughnessy

Adventur.es — Brent Beshore, Emily Holdman

Collaborative Fund — Morgan Housel, Craig Shapiro, Sophie Bakalar, Lauren Loktev

Footnotes:

[1] ETF: A tradeable security that tracks an index or basket of assets.

[2] We acknowledge that this is an oversimplification of a complex debate on the merits of active vs. passive. Furthermore, the intention is not to diminish the role of active management, which is provides critical social goods such as price discovery and liquidity. It would be a fool’s errand to predict the active vs. passive distribution in the next few years. We defer to Michael Mauboussin for more a formative debate on the topic. What we believe will be certain, however, is the demonstrable delivery of value to clients. If you pay a premium, you should be earning a superior return. Experimentation with fulcrum fees and active share are moving us in this direction.

Thank you to Morgan Housel, Meb Faber, Brent Beshore, Mike Dariano, Arjun Balaji, Sar Haribhakti, and Alex Hardy for feedback on this post.